She left Queen Victoria to become a North Dakota farm wife

Posted 3/07/25 (Fri)

By Tracy Briggs

ROLLA, N.D. — It’s the heart of many a fairy tale — a young woman rising from humble beginnings to a life of luxury in a grand palace.

But Marie Downing was Cinderella in reverse — leaving the opulence of Queen Victoria’s court in 1887 to become a modest farmer’s wife in rural America.

It was a colossal culture shock from the Victorian finery of London to the blustery acres of Rolla, Dakota Territory. Yet, in her old age, Marie said she did it for love and would do it again.

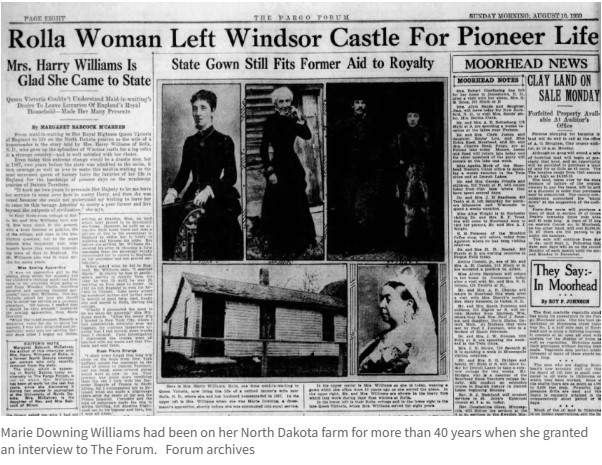

At 78, she granted an interview to writer Margaret Babcock McCahren, in which she reflected on her unusual journey from royalty to Rolla. The story that inspired this one was published in The Forum on Aug. 10, 1930.

From seamstress to royal attendant

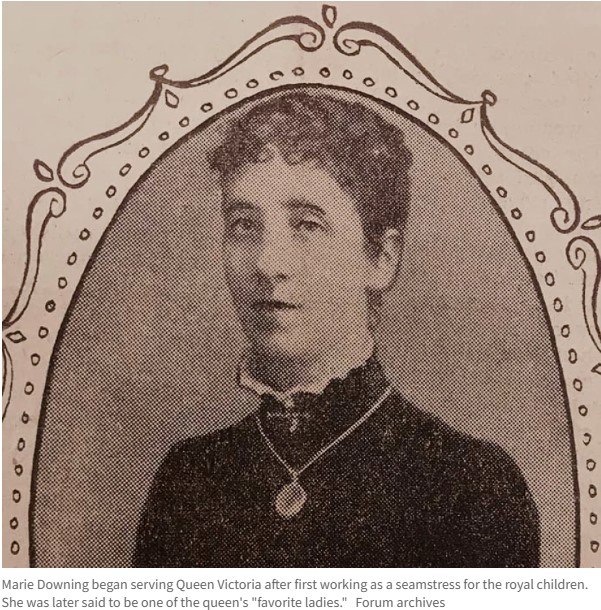

Marie first encountered Queen Victoria while working as an apprentice at a sewing shop, where she made clothing for the royal children. Her duties required her to travel to Windsor Castle, and one day, the queen took notice.

“When the royal request, literally a summons, came for me to serve Her Majesty, I was delighted and immediately went into her service,” Marie recalled.

As a maid-in-waiting, she always stood by the queen’s chair, anticipating every need. She witnessed discussions over state affairs with world leaders and intimate family moments with Prince Consort Albert and their nine children.

Marie received no salary but was provided clothing, food and numerous gifts, including diamonds that later helped purchase her North Dakota farm. One particularly cherished gift — a mantel clock — was originally a playful reprimand from the queen.

“It was my duty to choose suitable gifts for the queen to present to her callers,” Marie said. One such item, a timepiece, was to be given away, but after Marie arrived late for an appointment, the queen changed her mind.

“The queen took this and presented it to me, saying that perhaps this would help me be more punctual in the future,” she recounted. Later, the queen had the watch placed in a beautiful mantel clock case that eventually sat in her tiny log home in North Dakota.

Despite the controversy over her tardiness (Marie said the Prince of Wales made her late for her meeting with the queen), Marie became a favorite of the queen and was even loaned to her friend, Empress Eugenie. While traveling with the empress in South Africa, Marie is credited with saving her life.

Trading court life for the prairie

So how did a favored royal servant end up in Rolla, North Dakota?

It all started with a boy.

In 1879, Marie fell in love with a butler named Harry Williams, but he had dreams beyond serving the aristocracy. He wanted to be a landowner. In 1882, he set sail for Canada to buy a farm and begged Marie to follow him.

“It took me two years to persuade her majesty to let me leave her service to come here to marry Harry,” Marie said. “She was vexed because she could not understand my wishing to leave her to come to ‘savage America’ to marry a poor farmer and live beyond the outposts of civilization.”

The queen only consented on one condition: Marie had to return a marriage certificate proving she had married Harry Williams. (Because of her position with the queen, she was not allowed to marry him earlier.)

By 1887, Harry had abandoned his farming efforts in Manitoba and secured a claim west of Rolla. Marie finally set sail to join him. She was met with a massive mix-up upon arrival in New York. Customs officials insisted she had more trunks than she claimed.

“Upon investigation, I discovered the trunks were all labeled with my name and that Victoria had sent them,” she said.

Inside, exquisite clothing and jewelry lay tucked away — items befitting a palace rather than a North Dakota homestead. Nonetheless, Marie and the trunks were on their way.

“I shall never forget that long trip alone on the train from New York halfway across the continent in the dead of winter,” she said. “The bleak, snow-covered plains were so new to me.”

Once she arrived at the train station in Minnewauken, Dakota Territory, she was reunited with Harry, whom she hadn’t seen in five years. They immediately married in nearby Devils Lake and sent the marriage certificate to the queen. Then they boarded a horse-drawn sleigh for the 75-mile journey to their home — in 40-below-zero temperatures. The delicate parasol she had brought from England offered little protection from the prairie winds.

Marie was dismayed that their home wasn’t a pretty English cottage but a rustic log cabin with no doors or windows and a half-finished roof. Neighbors let them stay until the cabin was livable.

A touch of royalty in the heartland

As Mr. and Mrs. Williams settled into their new life, Marie became a local celebrity. Townsfolk eagerly visited to see and even touch the royal artifacts she had kept. She often lent gowns and jewelry to local brides, bringing some aristocratic splendor to the prairie.

Over time, the couple sold many of these treasures to finance their farm, buy supplies and purchase more land. Marie claimed the queen even sent letters and Christmas gifts — including a gold horse saddle that was later stolen from the barn.

The Williamses lived quietly on their farm for decades, returning to England only once in 1909. But Marie had no regrets.

“From the first, I liked the immensity of sky and prairie,” she said. “Even though I was sometimes lonesome in the early days when we had so few neighbors, I never wished to return to England or to the luxuries of the life I had formerly lived.”

Marie died on Dec. 5, 1933. Harry followed on March 23, 1940.

A flawed fairy tale?

While Marie’s story seems tailor-made for Hollywood, historian Helen Rappaport’s research casts doubt on some details . Rappaport suggests Marie may have been eight years older than she claimed and that she and Harry were already married before leaving England — a direct contradiction to Queen Victoria’s policy forbidding marriage among the maids in her service.

Further skepticism surrounds the exquisite gifts the monarch gave to her one-time maid. While Queen Victoria was known for her generosity, Rappaport wonders whether she would have sent such valuable items halfway around the world to a former servant who had worked for her for only four or five years. Why would she send items that would not be practical on the farm?

“What use would Marie Downing have for a ‘court train six yards in length’ that Queen Victoria had worn at state functions, or an inlaid Egyptian marble paperweight, or a black parasol lined with purple satin?” Rappaport writes. “Like it or not, one has to ask the question: Did Marie slowly and systematically purloin some of those ‘gifts’ from Victoria?”

Despite these inconsistencies, Marie’s royal belongings were undeniably authentic — relics of a royal household that somehow made their way to a remote North Dakota homestead.

Whether Marie Downing Williams embellished parts of her story or not, she undeniably brought a touch of royalty to Rolla. Some of her cherished belongings remain preserved at the Prairie Village Museum in Rugby, offering visitors a glimpse into the fascinating life of a woman who traded the grandeur of the palace for the quiet strength of the prairie.